According to the efficient markets hypothesis (EMH), it’s not possible to “beat the market”. Stock markets are price efficient which means that share prices always reflect all available information.

As such, financial securities always trade at their fair value, rendering it impossible for any individual (expert or not) to buy undervalued securities or sell overvalued securities for a profit above the benchmark performance.

But if this theory is true, it essentially means we have whole industries of professionals that are plying their trade for no reason at all. Hedge fund and mutual fund managers, traders and speculators, are all wasting their time trying to beat the market, and any outperformance from an investor can be attributed to luck alone.

Efficient Markets Hypothesis Key Assumptions

There are numerous proponents of the efficient markets hypothesis – with Chicago University Professor Eugene Fama credited with developing the theory in the 1960s. But if the efficient market hypothesis is true, then it must rely on the following key assumptions:

• That a large pool of investors are constantly analysing and valuing securities.

• That new information comes to the market independent from other news and in a random fashion.

• That stock prices adjust quickly to the new information.

• That stock prices reflect all available information.

On the face of it, these assumptions all look fairly believable and in a way it makes sense for financial securities to be perfectly efficient. But the simple truth is that financial markets have never been perfectly efficient and never will be.

Here are 10 reasons not to believe in the efficient markets hypothesis:

#1. Warren Buffett

Probably the most obvious reason to doubt EMH is the fact that so many investment professionals have succeeded in beating the market time and time again.

Probably the most obvious reason to doubt EMH is the fact that so many investment professionals have succeeded in beating the market time and time again.

Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has returned around 20% annually for over fifty years, while the market (as measured by the S&P 500 Index) has returned just 9.9% over that time.

He’s beaten the market 34 years out of 50, building a net worth of over $65 billion (as of July 2015).

In 1984, Buffett gave a speech at the Columbia Business School claiming that investors could still beat the market by a huge margin. He said:

“Ships will sail around the world but the Flat Earth Society will flourish. There will continue to be wide discrepancies between price and value in the marketplace, and those who read their Graham & Dodd will continue to prosper.”

He’s also quoted as saying:

“I’d be a bum on the street with a tin cup if the markets were efficient.”

#2. If markets were efficient there’d be no incentive to continue making them efficient

An excellent, recent article from Yale economist Robert Shiller discusses the idea of financial singularity, referring to a new book called The Incredible Shrinking Alpha.

The basic concept is that there could come a time where advances in financial technology and computer trading renders all financial markets perfectly priced. In this world it would be impossible to extract any alpha from the markets at all.

However, Shiller raises the point that if all financial securities were perfectly priced, then market participants would have no incentive to trade them. If there is no incentive for participants (electronic or otherwise) to enter the market, then there is no way those markets can then become efficient.

This is similar to the old economist joke:

“An economist walks by a twenty dollar bill on the sidewalk but decides not to pick it up, because if it were really there someone would have picked it up already.”

#3. Too many market bubbles & crashes

If financial markets were truly efficient, then it’s unlikely we would have seen so many spectacular market bubbles and crashes.

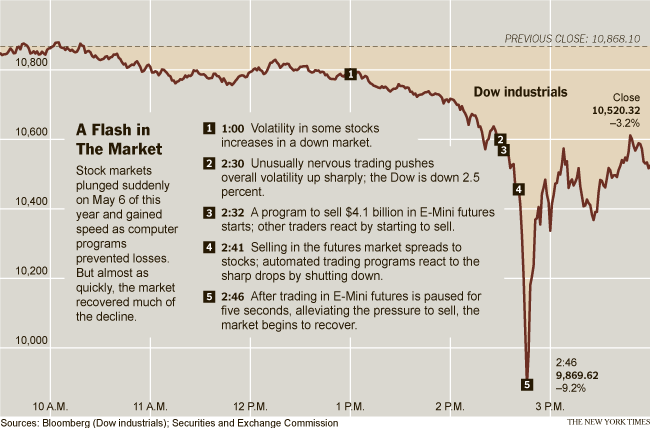

Consider the flash crash in 2010 where stocks dropped almost 10% in a matter of minutes. Or the incredible rally we saw in the Swiss franc in January. Or the recent 30% plunge in Chinese shares. There are almost too many to count.

Many of these market moves leave individuals and companies trading on hunch and emotion. Investors have been known to operate through fear and greed.

Meanwhile, major sell-offs are often exacerbated by forced selling, as investors liquidate their holdings at the very worst time in order to meet margin calls.

#4. Investors are human

Long tail events like market bubbles and crashes may be statistically believable, but the fact is markets are essentially run by people.

Investors make individual decisions based on experiences, belief systems, stories, hunch and emotion. Even high frequency trading systems are not immune to the bias of human behaviour, since they are built by humans in the first place.

#5. Information is rarely perfect

One of the key assumptions of efficient market hypothesis is that financial securities reflect all available information. But again, this seems unlikely when we consider some of the major market events, scams and frauds, that have occurred throughout history.

If financial securities were so perfectly priced then we would not have witnessed the billion dollar blow ups that occurred almost overnight for companies such as Enron, LTCM, WorldCom, and Lehman Brothers.

Available information is rarely perfect, so it seems unlikely that markets could be.

#6. Bruce Kovner

Warren Buffett may be the world’s richest investor but even Buffett’s suffered some bad years before, such as in 2001 and 2008.

There are other traders out there with track records so incredible, they’re hard to believe. Trend followers and CTAs are built on the very concept that markets are not perfectly efficient, and they’ve produced staggering returns over the years.

Bruce Kovner of Caxton Associates, is one trader who has managed amazing success trading a variety of different markets. Kovner was profiled in the original Market Wizards book by Jack Schwager and is said to have returned 28% annually.

Not only that, but Kovner is reported as only having one losing year throughout his career.

Img src: http://forbes.com

#7. Academics themselves don’t believe in efficient markets

While EMH is most definitely grounded in academic theory, there are plenty of academics who have their doubts. Even Burton Malkiel, author of a Random Walk Down Wall Street, recognises that market inefficiencies crop up from time to time.

Malkiel talked about such an efficiency in his book regarding certain closed-end funds trading at discount and gave precise details on how to profit from the anomaly. More recently, he’s been on the search for investment opportunities in China.

#8. Different investors have different investment motives

Lastly, the efficient markets hypothesis assumes that all investors approach the markets with the same objective. Investors wish to buy low and sell high, thus earning a profit from their transaction.

However, the problem with this concept is that market participants are all different and each one has a different motive for buying or selling a security.

Fund managers

Many institutional investors and mutual fund managers for example exhibit a follow-the-herd type mentality. They buy similar baskets of stocks in order to protect themselves from ‘losing face’ within the industry.

Because if you’re a fund manager it’s much better to say you lost -10% on the year, when everyone else lost -10%, than to say you lost -5%, when everyone else made 10%.

As a result, fund managers tend to pick one or two key investments, then fill up the rest of their portfolio with all the same stocks.

Hedging, market timing

Likewise, many investment strategies are not based purely on extracting profits from the markets. Large corporations and banks may put on big positions in order to balance their books and hedge their other investments and expenses.

Pensions and other investment vehicles may not be interested in timing at all, they simply invest in the market at regular intervals with little regard for information or price efficiency. Forced buying and selling are also moments when market participants are unconcerned with price.

#9. There are too many gamblers and speculators

Furthermore, some investors may not be interested in investing at all and are only interested in gambling.

A cynical point of view suggests that some investors do not even care whether they lose or win; they get their thrill from playing the game.

When you have these types of investors in the market it does not make sense to say that the market can be completely efficient.

#10. Government intervention causes imbalances

Lastly, markets are too often interfered with by government action to render them completely efficient.

When the Swiss National Bank took away exchange controls on the Swiss franc earlier this year, mayhem ensued and several forex brokers went into liquidation.

When the credit crisis came to a head in 2008, the Federal Reserve saved many institutions from going under as the knock-on effects would have caused severe consequences for the financial system.

These ‘too big to fail’ institutions were unjustly rewarded for taking on too much risk.

The ensuing policy of excessive monetary stimulus and propping up of banks has only contributed to skewed incentives within investment banks and led to an economy filled with imbalances.

Yeah, werll said.

An unstated assumption in EMH is that all investors/analysts process information instantaneously and perfectly accurately. They don’t. I am no Graham or Buffet, not even a Bob Yerbury, but I have earned a living for forty years by being better at it than the average.

Also I believe in death and taxes – the EMH does not. If a share price is overvalued by less than your tax liability on selling, why should you sell? If you are 99, what good is a long-term growth stock with a nil yield to you (unless it has an IHT exempotion)?

Great point re: tax harvesting.

I probably should also have mentioned the different forms of EMH (weak, semi strong and strong). Congratulations on beating the market 🙂