I have spent much of the morning reading Misbehaving: The Making Of Behavioral Economics by leading expert and professor, Richard H. Thaler. This is a book that offers a full introduction into behavioral economics whilst managing to still be entertaining and readable.

I have spent much of the morning reading Misbehaving: The Making Of Behavioral Economics by leading expert and professor, Richard H. Thaler. This is a book that offers a full introduction into behavioral economics whilst managing to still be entertaining and readable.

The book is filled with exercises, puzzles and even jokes (like the one about the efficient market hypothesis and the $10 dollar bill) which makes reading it enjoyable rather than a slog.

Two economists are walking down the street when one points to the ground and says, “Look, a ten dollar bill!”

The second economist replies, “That’s crazy. If that was a ten dollar bill someone would have picked it up already.

Unsurprisingly, the chapters on finance and the inner workings of the stock market are what interested me the most and I gained new insight about economic theories from reading this book.

Efficient Market Hypothesis or Behavioral Finance?

Efficient market hypothesis states that there are no free lunches in the finance world. Financial markets are nearly always correctly priced (at least 90% of the time according to Fisher) therefore anyone who is able to beat the market over any considerable length of time must have done so either by luck alone or by taking an inordinate amount of risk.

This theory was first credited to Eugene Fama and remained the predominant view amongst economists for many decades. Although not perfect, it was the most rational theory and one that was difficult to prove wrong.

In more recent years, EMH has been, in a sense, super-ceded by behavioral economics.

Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics is based on the premise that markets are driven by humans and humans are a complex bunch who do not always act rationally and in their own best interests.

There are numerous examples to support this view and Thaler provides plenty in his book.

For example, there is the consumer who will drive 20 minutes across town to save $5 on a $15 electric kettle but won’t bother making the same trip to save $10 on a $200 TV.

Another good example from the book is a game that Thaler ran for the Financial Times where readers had to guess a random number from 0-100 based on the popularity of other readers choices.

All in all, the studies and experiments repeatedly show that humans do not always act rationally even in the face of complete information and as a result, financial markets cannot be entirely efficient if comprised of human participants.

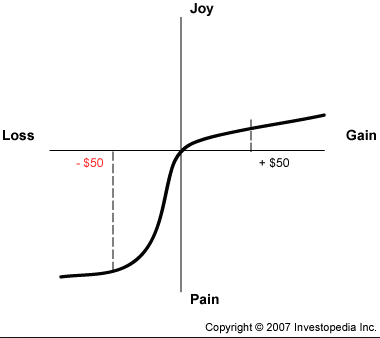

Indeed, one of the key findings is that, as humans, we detest losses much more than we appreciate profits. This causes an asymmetrical balance where we become too risk averse with our winners, while risk-seeking with our losses.

This is clearly shown in the gambler or financial trader mentality.

When we have a winning bet we feel compelled to take some profits off the table and protect what we have. Whereas when we have a losing trade, we are often compelled to take even bigger risks just to get back to break even! We hate losing far more than we love winning.

Principles like these are the reasons financial markets do not always act in rational ways and here there are also many examples to choose from; the Dotcom bubble which saw the Nasdaq boom then lose a third of its value, the stock market plunge of 1987, and the sub-prime crisis of 2008. All these bubbles and busts ask very hard questions of the efficient markets hypothesis.

Closed-End Funds

Anyway, it was not actually my goal to write too much about behavioural economics and EMH in this post. I also wanted to talk about closed-end funds which make an appearance in Thaler’s book in section 7.

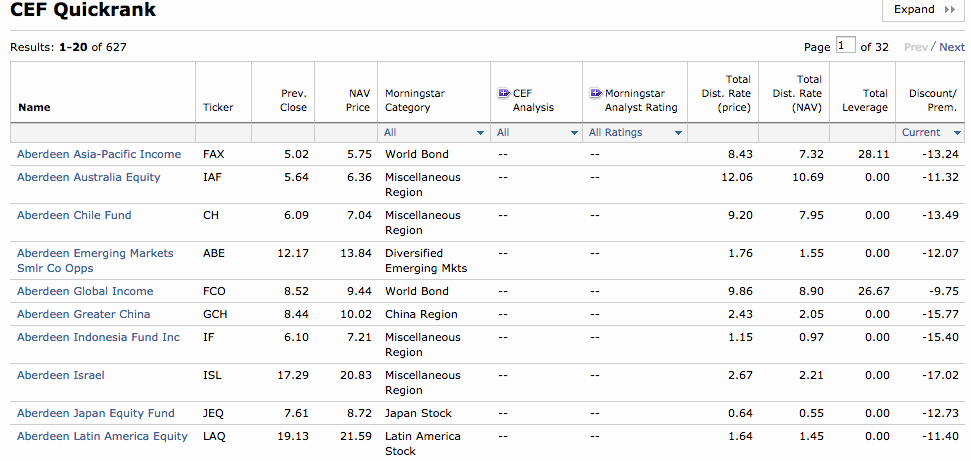

Thaler states that closed-end funds clearly demonstrate that the market is not efficient. He says this because there are many closed-end funds (CEFs) that trade at a discount to their net asset value (NAV) and continue to do so for weeks or even months on end, giving investors a risk-free opportunity to profit from the mis-pricing.

The idea is that a closed-end fund might consist of a variety of assets but, for whatever reason, trade on the open market at a value less than the sum of it’s parts.

For example, imagine a closed-end fund that has 100% of it’s capital invested in Apple shares while Apple trades at $100 per share. But instead of being available to buy on the market at $100, the fund is now trading freely at only $90 per share, which equates to a discount of 10%. Since the fund is wholly invested in Apple, it should be valued the same as the business (perhaps with a discount to take account of fees and the possibility of mis-management).

Browsing the website Morningstar, you can find numerous examples of these closed-end funds trading at discounts of 10%, 20%, and even 30%. If Thaler is right, then these closed-end funds are undervalued. Their discounts will surely narrow over time with the funds moving closer to their NAV, therefore giving investors an easy profit.

As you can probably tell, I am by no means an expert in any of this but I do find it an interesting concept and it’s one that Burton Mankiel also recommended in a Random Walk Down Wall Street.

The problem as I see it, however, is that many of these funds trading at discounts have been trading at a discount for some time. Boulder Growth And Income Fund $BIF, for example, is a general equity CEF with a 22% holding in Berkshire Hathaway (as well as several other large financial stocks).

BIF currently trades at a 22% discount to NAV suggesting that it’s entire holding of Berkshire Hathaway is not reflected in the share price (unless I’m mistaken of course which is entirely plausible).

However, even if the fund is undervalued, the following chart shows how the fund has maintained this wide discount consistently over the last five years:

Here, the green line shows the NAV that the fund “should” be trading at and the blue line marks where the fund’s actual price. So you can see that the fund has traded at a significant discount to NAV for some time.

So, just because a closed end fund is trading at a discount does not necessarily mean that the discount will narrow. Perhaps, the idea then is to look for smaller, incremental changes in the discount rather than looking for the discount to close completely.

Anyway, this is just one example. Overall, the concept is incredibly interesting and offers just another idea for the smart investor to think about.